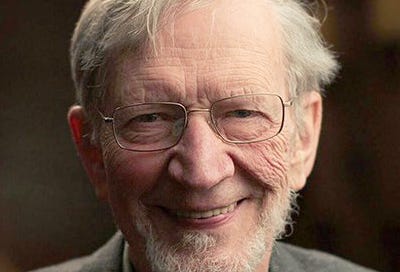

This morning I returned to Knowledge and Christian Belief by Alvin Plantinga, the Templeton-prize winning genius who’s arguably one of the best prose-stylists in modern philosophy.

Tucked in at the beginning of the book, in a throwaway paragraph, Plantinga makes a wonderfully incisive comment about dismal quality of much academic prose-writing.

In a disc…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Going Awol to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.