I. What Happened

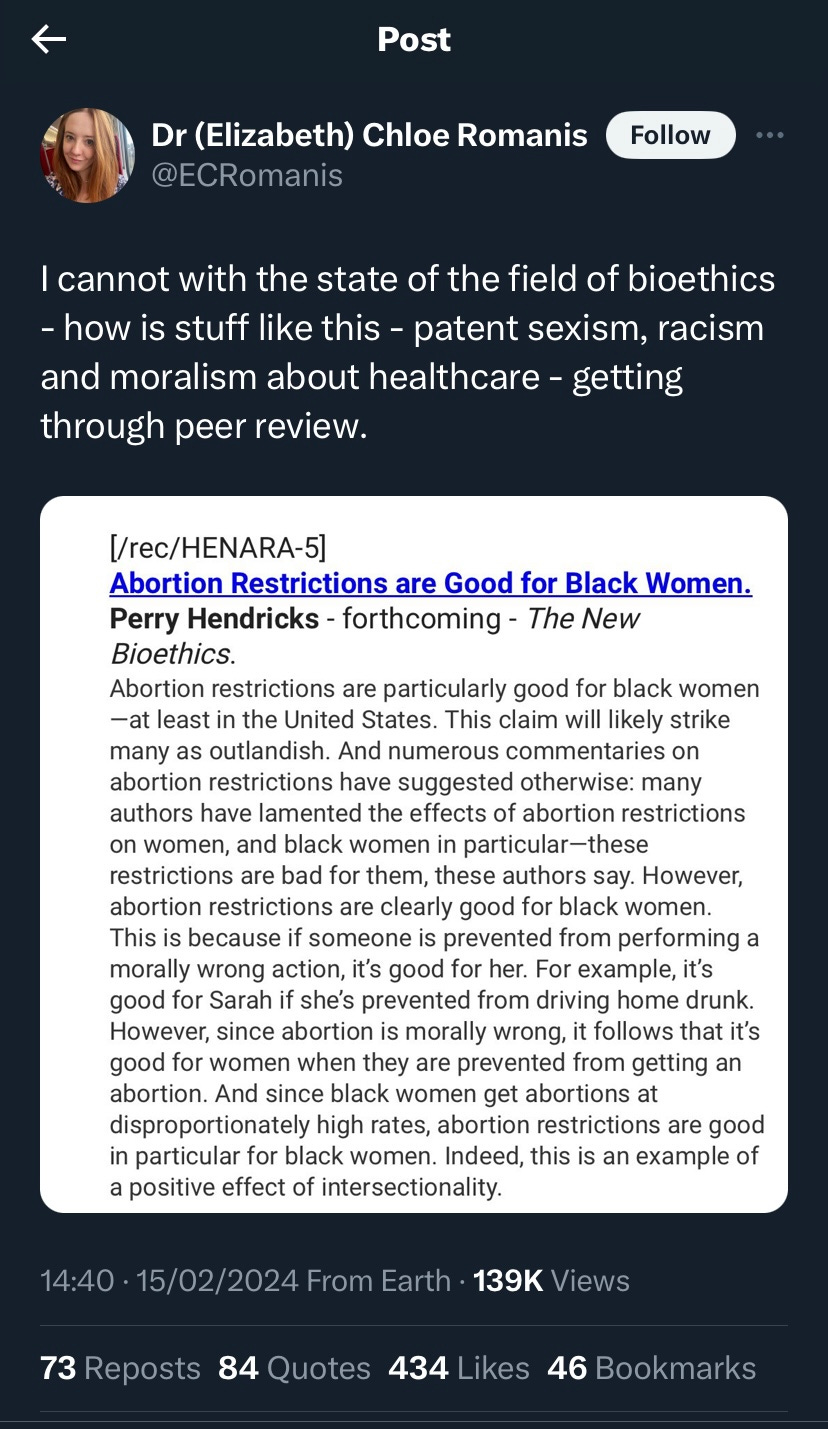

The other day, Perry Hendricks—philosopher, nice guy, and now officially “Dr. Hendricks” (he’ll machete you to death if you call him that)—uploaded his 600th academic paper on abortion, available on PhilPapers.org as a pre-print. A screenshot of the abstract was tweeted out, and people got angry because, well. . .

Responses ranged from th…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Going Awol to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.