A Theory of Online Trolling

...

Philosopher Jeffrey Kaplan has a theory of online trolling that I think is pretty good. To theorise about the “nature” of any social phenomenon, it’s prudent to start with one’s nose to the ground, sniffing out its paradigmatic features and then sweeping them into a pile. When it comes to trolling,

Trolls typically find trolling fun;

Their targets typically find it frustrating;

Trolling can be a one off speech act (haha, ur mom!), or sustained and continuous siege (ur mom ur mom ur mom ur mo—);

The hotbed of trolling is the internet.

For a concept as fluffy and puffy as “trolling”, there is unlikely to be a perfect definition of the thing, one that grabs trolling by its necessary and sufficent lapels and has nothing to fear from counter-examples. Still, some definitions are worse than others, and Kaplan’s is better than most.

On Kaplan’s best attempt at an analysis, “[a] singular or group agent A trolls an audience B by making an utterance or series of utterances that

is likely to elicit from B a reaction r that A regards as mockworthy, and

is believed by A to be likely to elicit r from B, and

is primarily intended by A to elicit r from B.”

More plainspokenly, if you—or your friends—tweet at—or spam—some vegan with pictures of crispy bacon because you think it’s likely that they will say “okay, guys, very funny, but I do think there’s a strong case that industrially farmed bacon is ethically probl—” and you primarily intend to evoke this reaction, because you think it’s hilarious, because you are Satan dressed up as a person, you have engaged in trolling, and you may wear a little sticker that says so.

When trolling is discussed, it is nearly always in the negative. Southpark did a season on trolling, and it resulted in Denmark trying to destroy modern civilisation. This reputation is, of course, deserved.

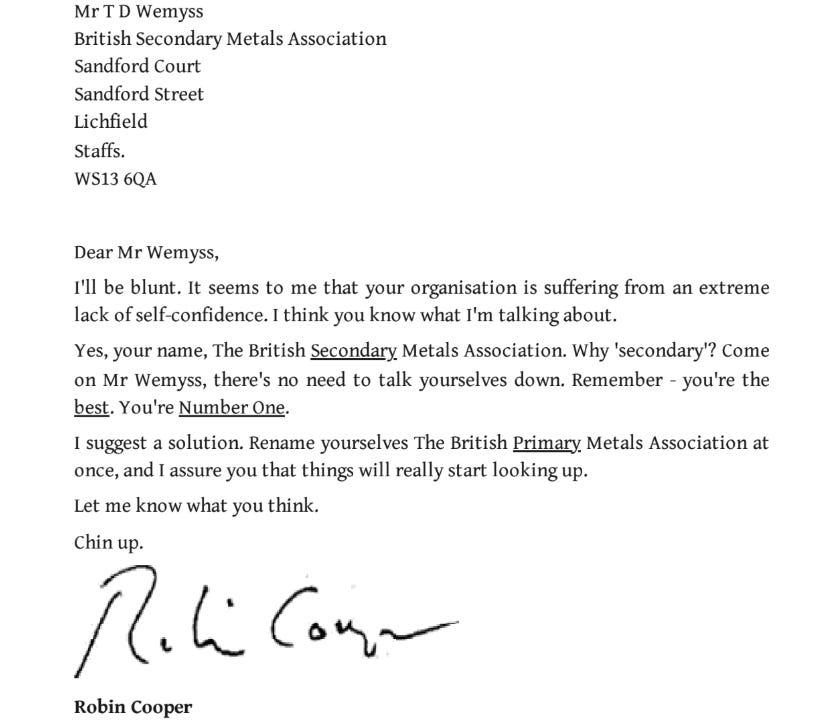

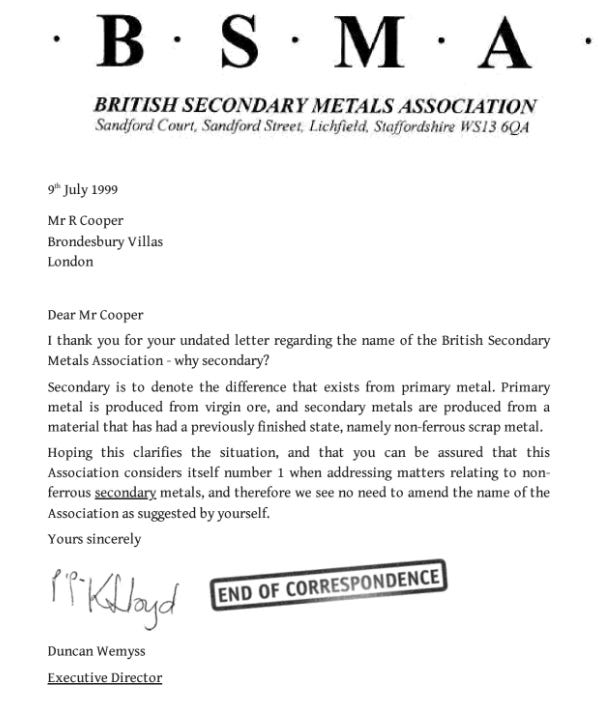

But there are examples of virtuous trolling, and not just in the boring, moral philosopher’s limit cases where you can troll Hitler to save five relatives from a fat man driving a trolley. In the toilet bookshelf of one of my relatives there was book called Robin Cooper’s Timewaster Letters, which I would read to pass the time in there. It’s an anthology of the correspondence between this legend called Robin Cooper and various companies and associations that he would post letters to, pitching proposals.

Come on, this is funny, it must be fine. Cooper was a troll per Kaplan’s definition, but he did it in a tasteful, artful way: his bits were sincerely amusing, and although he was trying to squeeze a “mockworthy” reaction out of the stuffy HR people at the British Secondary Metals Association, he allowed each correspondence to end when his victims stopped writing him back.

But in general, the conventional wisdom on trolling seems right. In “I wrote this paper for the Lulz: the ethics of internet trolling”, Ralph DiFranco suggests that what’s often wrong with trolling is the way it disrespects its targets. In particular, trolls violate all manner of conversational norms—norms their targets would prefer to adhere to—in an attempt to alarm, disturb, frustrate, and take time out of their busy days; this is prima facie disrespectful, and fails to treat the victim as an equal in the interaction.

In addition to being wrong for these spooky non-consequentialist reasons, there is the familiar consequentialist consideration that winding people up makes them feel bad.

Trolling is sometimes used not primarily to elicit a mockworthy reaction, but to launder one's sincere or semi-sincrere views into the public square through a protective layer of irony.

https://philarchive.org/archive/BARAOT-9

Aristotle on trolling.

Seemed relevant.